My introduction to liver was perfectly pleasant. There was a period in my childhood when liver was a routine dinner entrée. This was when my mother had 6 children under the age of 10 and was assisted by a mother’s helper. My memory is a bit hazy on this point, but I don’t think that we children ate dinner with our parents. My father was a printing salesman, and routinely got home around 7 PM, and I think that my mother made a separate meal for the two of them, while a rotating crew of mother’s helpers was assigned to children’s dinner. There were a lot of them. There was the mother’s helper my mother fired because she seemed too weirdly religious – she had taped a sign “Have you prayed about it lately” in the bathroom just opposite the toilet. Then there was a tiny scrappy woman named Ada, whose false teeth were fascinating, and who would go the to bars at the nearby naval base and come home drunk. She also tried to play the accordion, and at night I remember hearing a tortured version of “Roll Out the Barrel” emanating from her bedroom. But mostly there was a series of big-boned Finnish women from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. My mother cleverly put in an ad in the UP Mining Journal, and then shared her responses with friends, so that our town had a nucleus of Finnish women – my mother referred to them as “300 pound wonders.” They stayed with us during the school year, and then disappeared to their own families during summer vacation.

I think that Matty was the 300 pound wonder who had a fondness for liver and incorporated it into our limited menus. When Mattie was replaced by Aili, liver totally disappeared from my life for a good 15 years. But during that short period I loved our liver meals, in part because they were so visually stunning. The sliced liver was an  assertive deep rich brown color, the kind of brown that royalty wears, or the color of the most beautiful horse you could ever imagine. The liver certainly didn’t have any unpleasant associations – it wasn’t pale or timidly brown, or the color of mud or dirt. And then the liver was always served with a beautiful rich saffron-colored squash, again the color of royalty. I remember dipping the bite of liver into the pureed squash and marveling at the exquisite color combination as the saffron draped over the deep brown. I hoped that my last name of Brown was the same color as a liver.

assertive deep rich brown color, the kind of brown that royalty wears, or the color of the most beautiful horse you could ever imagine. The liver certainly didn’t have any unpleasant associations – it wasn’t pale or timidly brown, or the color of mud or dirt. And then the liver was always served with a beautiful rich saffron-colored squash, again the color of royalty. I remember dipping the bite of liver into the pureed squash and marveling at the exquisite color combination as the saffron draped over the deep brown. I hoped that my last name of Brown was the same color as a liver.

I don’t think I knew exactly what liver was, and certainly didn’t realize that I myself was the proud owner of a liver. My attempts to come to grips with being a carnivore didn’t include liver and only focused on muscles as meat. Standard issue hamburgers were far removed from the barnyard cows but eating chicken could be unsettling. Chicken breasts were generically referred to as “white meat,” thus removing any direct anatomic association, but chicken legs were a different story. They actually looked like legs, and you could imagine them still attached to a vibrant chicken, proudly strutting around the chicken yard. And then there was the Easter lamb, not the meat itself, but the very anatomically correct cake my grandmother served. As much as everyone liked cake, it was difficult to get enthusiastic about diving in. What were you supposed to do, just chop off the lamb’s head and let it roll around your plate? I remember an untouched Easter lamb cake languishing in my parent’s freezer for many years.

difficult to get enthusiastic about diving in. What were you supposed to do, just chop off the lamb’s head and let it roll around your plate? I remember an untouched Easter lamb cake languishing in my parent’s freezer for many years.

Then came the cadaver in my first year of medical school. With the body splayed open and each muscle carefully dissected, I had to confront the stark fact that I was a carnivore. I remember teasing out the nerve and artery that ran beneath the bottom edge of ribs, and then that night at dinner I found the exact same anatomy on my barbecued pork ribs. I’m always going to be a carnivore since I don’t think that I could ever give up my bacon, but it is easy to divorce yourself from the animal kingdom when the meat is butchered and carefully wrapped up. It is more difficult when you realize that you are personally carrying around the same cuts of meat.

And then there was the liver. My cadaver liver, frankly, was a bi dinged up and shrunken with formaldehyde, but then I became better reacquainted with my favorite childhood meal when I started doing autopsies as part of my pathology residency. A fresh human  liver looks exactly the same as the calf’s liver in the meat department. And in that moment I realized that I could never ever eat liver again, not even if it was the last thing on earth. The specter of cannibalism was the major issue, but as I progressed through medical school, I grew to hold this humble organ in the highest esteem and felt it would be too disrespectful to eat one.

liver looks exactly the same as the calf’s liver in the meat department. And in that moment I realized that I could never ever eat liver again, not even if it was the last thing on earth. The specter of cannibalism was the major issue, but as I progressed through medical school, I grew to hold this humble organ in the highest esteem and felt it would be too disrespectful to eat one.

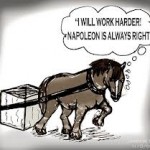

It turns out the all vertebrates have a liver, and it is the largest solid organ in the body, larger even than the brain. Its shape is determined by the constraints of anatomy. The liver of the snake, for example, is long and thin, but the human liver consists of two big honking lobes nestled under the ribs on the right. And the liver is a total workhorse. I am reminded of the character Boxer in George Orwell’s allegory Animal Farm. Boxer is a loyal horse, representing the hard working proletariat in revolutionary Russia. He takes on any job at the Animal Farm and his mantra is, “I will work harder.” This is the epitome of the liver.

Sure the heart is a vital organ, but it only does one thing, beat (and thank god for that). If the heart falters, there are many drugs and devices that can whip it back into shape. In contrast the functions of the liver go on forever and there are no drugs to improve liver function. This vital organ sorts out the incoming nutrients delivered by the intestines, manufacturers vital proteins, manages the supply of glucose, produces bile that seeps into the intestine to aid in fat digestion, removes fatigued blood cells and detoxifies all sorts of drugs and nastiness that we throw at it.

Another great thing about the liver is that it can regrow whole new lobes. We are amazed by the lizard who can regrow a tail, complete with muscles, nerves and bone, but you can whack out half the liver and it will grow back and eagerly assume all its complicated responsibilities, good as new. What a fabulous spare part factory. If you are in the unfortunate situation of having a loved one who needs a new liver, or you have just suffered a gunshot wound or some other grisly trauma, you’ve got enough liver to spare.

The loyal liver simply absorbs all the abuse that we heap on it. As the story of Animal Farm progresses, we see Boxer working harder and harder, but we also suspect that this unquestioning loyalty will eventually be his doom. When things start to go badly on Animal Farm, and the head pig Napoleon starts to execute other animals, Boxer can only naively say:

“I would not have believed that such things could happen on our farm. It must be due  to some fault in ourselves. The solution, as I see it, is to work harder.”

to some fault in ourselves. The solution, as I see it, is to work harder.”

Though livers do have a weakness for viruses, it’s hard to destroy a liver on your own. You can douse it in toxins on a daily basis and it just keeps chugging along. I even remember one microscopic slide from an IV drug user where I spotted small crystals of glass embedded in the liver cells. At the beginning of Animal Farm, Old Major gives Boxer some ominous advice about this unrequited loyalty:

“The very day that those great muscles of yours lose their power, Jones will send you to the knacker, who will cut your throat and boil you down for the fox-hounds.”

And that is exactly the fate of the liver, when exhaustion sets in and the liver finally fails, all you can do is cut it out and pray that you can quickly find a new one.

I have grown to love and respect my liver, and I am not the only one. In his book, “The Lives of a Cell,” the noted essayist and physician Lewis Thomas paid the following eloquent homage:

“I’d sooner be told, forty thousand feet over Denver, that the 747 jet in which I had a coach seat was now mine to operate as I pleased; at least I would have the hope of bailing out, if I could find a parachute and discover quickly how to open a door. Nothing would save me and my liver, if I were in charge. For I am, to face the facts squarely, considerably less intelligent than my liver. I am, moreover, constitutionally unable to make hepatic decisions, and I prefer not be obliged to, ever. I would not be able to think of the first thing to do.”

I would love to actually see my liver at work, glistening a deep rich brown in the upper right quadrant, pulsating slightly with the blood flow, and bobbing up and down with respiration. I remember working in the pathology lab when I got a request to photograph a surgical specimen – an old, tired and lumpy uterus that had been removed in a hysterectomy. From time to time we would photograph specimens, but only if they posed some problem of orientation or were particularly interesting. This ho-hum uterus did not qualify so I ignored the request. And then the word came down from the OR; the surgeon insisted that I photograph this thing since it belonged to a trustee’s wife. I dutifully made the vanity shot, and imagined that the trustee’s wife, who was evidently used to getting her way, must have had many children and had developed a sentimental attachment to her womb. And thinking of my liver, I understood. When I had my gallbladder removed, I had enough wits about me to ask the surgeon to save the stones as a memento, but now I regret that I didn’t give one of the OR nurses a camera and ask her to take a picture of my magnificent and loyal organ hard at work.

The missing words in the following poem are anagrams (i.e. share the same letters like spot, post, stop) and the number of asterisks indicates the number of letters. Your job is to solve the missing words based on the above rules and the context of the poem. Scroll down for answers.

One meal stands out among all the childhood dinners I ever ate.

It’s that shimmering ****** slithering across my plate.

I think of my own in my abdomen where it bobs and quivers.

And the deep respect I have for all hard working ******.

And the ****** lining is that we have enough liver to spare.

We can donate some because there’s more than enough to share.

*

*

*

*

*

*’

*

*

Answera: sliver, livers, silver

Follow Liza Blue on:Share: