One of the books on the reading list for my upcoming writer’s workshop is “The Art of the Personal Essay,” a 700+ page anthology of essays ranging from Seneca (AD3-65) to present day. I decided to pick my selection by riffling through the book and asking Nick to say stop. The first random essay was by GK Chesterton, and the second by Virginia Woolf. I was pleased to make the acquaintance of Chesterton, who is quoted by Evelyn Waugh in the novel “Brideshead Revisited,” describing the unshakeable pull of religion even among lapsed believers:

“I caught him (the thief) with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread.”

This quote has made my list of favorite lines from a book, but I knew nothing further about  Chesterton. I was of course familiar with the name Virginia Woolf, and knew enough to spell her last name with two O’s, but knew nothing of her writing.

Chesterton. I was of course familiar with the name Virginia Woolf, and knew enough to spell her last name with two O’s, but knew nothing of her writing.

These two random essays seemed very similar – Chesterton buys a piece of chalk to draw a picture on a piece of brown paper, and Woolf goes out on a evening walk to buy a pencil. Reading just these pieces the aspiring essayist could believe that the secret to success is a closely drawn description of a trivial errand interwoven with some philosophical observations. In fact, this seems like very good advice, and as I sit here at my desk, I cast my eyes about for some triviality. I am lucky to have a panoramic view of a prairie, and multiple nature-themed essays come to mind, but they seem just too grand. I need something smaller. Perhaps if a bird suddenly thudded into the window, I could describe my tender stewardship in finding the bird’s final resting place as I watch its agonal flutters. I could segue into a commentary contrasting the end-of-life care of animals vs. people, and the relative merits of sudden violent death versus a slow trickling ebb. But that is just too heavy, man. I will leave that subject aside for now, though I will retain “Agonal Flutters” as a suitably provocative title for when I am older and the issue is more pressing.

I get up and walk to the window and peer out into the two deep window wells to see if there are any trapped animals that could provide me with the small moment. No luck. One year we had a bizarre influx of frogs, presumably due to some once-in-a-decade coincidence of moisture, temperature and several other intertwined X factors. We routinely found frogs in our finished basement and were puzzled as to how they got there. My sister-in-law was startled from her pleasant respite on the porcelain throne by a nonchalant frog hopping by. My cousin Edie put her suitcase down in the basement guest room and several days later was saddened to discover she had inadvertently crushed a frog. I reached into a basket of yarn and found a mummified frog, who was probably initially thrilled to find such a soft landing spot, and then desperate as he became fatally entangled in the fine wool. The window wells were filled with live frogs. My nephew would jump in and pitch the frogs out onto the moist grass. I could hold a frog and look right into his bright eyes and imagine what strange fate brought us together, perhaps describing how the frog suddenly tumbled into the abyss, the struggles to eke out a living among the dank stones, and his lucky escape. This is exactly the strategy that Woolf uses in her essay. She imagines the lives of the strangers she passes on the street based on small snippets of overhead conservation – the dwarf buying a new pair of shoes, the quarreling shopkeepers or two blind men. Woolf is indeed impressive – she turns a simple act of buying a pencil into a tour de force spanning 9 pages and some 5,600 words. In contrast, I typically run out of things to say after about 1500 words.

I find no inspiration in the window wells today, and sit back down at my desk. I lean down to find my other shoe and for a moment rest my eyes on my foot. I need look no further, there it is – the perfect topic for this writing exercise of turning nothing into something.

Specifically, I want to focus on my left foot, since to dissect my right foot would require a description of the unhappy marriage of fungus and a toenail, more formally known as onchymycosis, a subject that flirts with the uncomfortable fringes of too much information. My left foot is a bit scuffed up from a morning of gardening but otherwise unsullied and suitable for discussion. I find the format of my toes most satisfying with a steady and even progression from the stalwart big toe to the diminutive pinky, which perfectly snuggles its neighbor. Other foot styles, with a second toe longer than the first, or a knobby and gangly big toe, don’t have the same panache. While I have no illusions that I could multi-task as a foot model, I will say that I have absolutely no complaints about my feet. They have served me well, and I try to do right by them. I have never crammed then into pointy shoes or teetered on stiletto heels.

Summers we spend hiking in the untrampled woods of the upper peninsula Michigan. The trails are well-worn, but sometimes I wonder if I just stray off the trail a little bit, maybe as little as 100 yards, I could be the first ever human to make a bipedal imprint in the leaf litter, the first in the 50,000 years that humans have been in North America. Neil  Armstrong is justifiably proud of his one small lunar step, and I would imagine a picture of the first dusty footprint hangs prominently in his office. But even though I am relentlessly earthbound, I would like to think that there might be one or two unique footprints in a lifetime of millions.

Armstrong is justifiably proud of his one small lunar step, and I would imagine a picture of the first dusty footprint hangs prominently in his office. But even though I am relentlessly earthbound, I would like to think that there might be one or two unique footprints in a lifetime of millions.

I bend down to hold my thumb next to my big toe, anatomically known as the hallux, and they look suitably similar. My parents had a neighbor who was in a terrible farming accident involving a hand and a thresher, the way farmers do. The solution was to surgically move the hallux to the raggedy hand and repurpose it as a thumb. My big toe would be a bit oversized for my hand, but otherwise I would welcome the gerry-rigging.

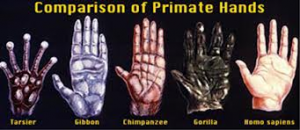

While we might think an opposable thumb is the hallmark of being human, I know that I should really value my two feet planted firmly on the ground. Evolutionary anthropologists point out that a bipedal gait is the defining characteristic of humans. Other primates have opposable thumbs after all, but we are the only mammal that walks, and walking was the prerequisite for our other treasured attributes, such as free hands to make tools, and breathing that could be uncoupled from our gait, permitting the development of speech. And once we started walking, we could hunt for protein rich meat, and then, properly nourished, our brain really took off.

What a marvel my foot is – with some 26 bones, 33 joints and over 100 muscles, tendons and ligaments. Lest we get too caught up in the wonders of evolution, I would like to point out that evolution does not have an agenda in mind and does not seek excellence, but only something just good enough to provide an edge in that jungle out there.

A good example of this phenomenon is the good but not great bipedal sense of balance. I know my balance is poor, and growing more tenuous with age. Just this morning I tripped over a hose at the garden supply store and fell into a murky puddle. I suffered nothing more than embarrassment and a skinned knee whose scab might be fun to pick at in a week’s time. But perhaps tripping was just a careless accident related to sloppy footwork, and I should be grateful to my sense of balance for saving me from a more disastrous header. Now I’m all cleaned up and sit watching the acrobatic swallows outside my window and jealously think of the flamingo who finds hours of relaxation standing on one foot. When I stand on one foot, I bob and waver. If I close my eyes it gets worse and the other foot touches the floor in less than a minute. But I don’t blame my feet. As I look down I see the muscles sequentially quiver in a heroic attempt to stay upright. My toes arch and clench and the big toe is working so hard. It would definitely be a sacrifice in balance, if, god forbid, the toe ever needs to become a thumb.

That’s all I need to say, and yes, kind readers, as predicted this essay clocks in at about 1500 words.

The missing words in the following poem are anagrams (i.e. share the same letters like spot, post, stop) and the number of asterisks indicates the number of letters. Your job is to solve the missing words based on the above rules and the context of the poem. Scroll down for answers.

Let’s say you ******* to be writer, but then you lost your way.

You developed writer’s block – couldn’t think of what to say.

Others found success in disclosing dark thoughts from the depths of *******

But you’re happy and peppy and there’re some things you just don’t want to share.

So think small – Chesterton became famous writing about a simple piece of chalk

And Virginia Woolf was ******* for her (well-written) essay about an evening walk.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*Aspired, despair, praised

Follow Liza Blue on:Share: