I have been well-trained to assimilate the ICK factor with equanimity and good humor. As a pathologist, I have performed hundreds of autopsies, uncoiling yards of slippery intestines and carefully scooping out their contents. When assigned to the operating room, I analyzed all the bits and pieces that were removed during surgery – lungs, breasts, livers, hips, stomachs, spleens. On a busy day I could almost sew all the parts together into a complete person. But nothing prepared me for the concept of medical maggots.

I do not have any positive association with the creatures – my most frequent encounters are sightings of road kill, where a seething swarm of maggots can collapse a once vibrant fox into a one-dimensional pile of detritus. And there was that time when I was working in the city morgue and was tasked to determine the causes of death of corpses who had died outside of a doctor’s care. Typically these were not the violent deaths that were the fodder for TV crime show procedurals, but rather the quiet deaths of unfortunates found dead in some sort of flop-house or park. One day, an assistant asked me to help process the latest arrival. At first the corpse looked oddly jittery, but then I realized the entire body was alive with maggots. I was new to the morgue and hoped that this was not some sort of hazing ritual, so I tried to stay calm.

“Look at the eyes,” the assistant said, “That’s the softest part of the body, and that’s what goes first.”

I placed my arm on the wall to steady myself and tried to take a professional peek. Sure enough, the eye sockets were sunken and empty. I was used to seeing death, so that no longer made me queasy. And I don’t think it was the maggots themselves. It was really what they represented – a solitary death with the body lying unnoticed in the depths of the park for at least the four to seven days it would take a fly to find the body, lay eggs, followed by hatching into the larval maggots. The maggots then live for another 4 to 7 days, so the body could have remained unclaimed for several weeks with multiple rounds of egg-laying and hatching. The situation suggested a desolate and homeless life, one without friends or family to even notice that this man had disappeared. A life that had fallen far short of even the most limited expectations.

I have not thought much about maggots since then. (Even the word sounds unpleasant, with the hard “g” and the palatal “t.” Imagine how much more pleasant if the word was pronounced with a soft “g” – something along the lines of “mah-jo.”) But there it was sitting on my desk- an article describing the intentional use of maggots to clean wounds that just refused to heal – wounds from surgery, trauma, diabetes or poor circulation. As a medical consultant, I had been asked to consider whether health insurance should pay for the costs of maggots to treat wounds. There were a couple of laboratories that specialized in breeding antiseptic maggots for the explicit purpose of wound healing. These laboratories wanted to designate their maggots as medical devices, lumping them with other high technologies such as pacemakers or hips.

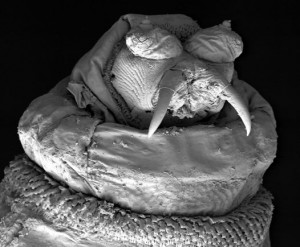

The removal of dead tissue is referred to debridement, which is a crucial step to promote wound healing. Basically healthy tissue cannot regrow until the dead tissue is removed. Surgeons typically perform debridement, but it can be difficult to distinguish between living and dead tissue. However, maggots only feed on dead tissue. First they use their mouth hooks to tear away the flesh, then secrete enzymes that dissolve the bits and pieces. Finally, the maggots sop up the nutritious liquid. When placed into a wound, the maggots scurry around into the cracks and crevices of a wound beyond the keen eyes and nimble fingers of the surgeon.

Much of the literature on medical maggots has been authored by a Dr. Ronald Sherman, the head of California-based Monarch Labs that breeds and distributes the larvae. He points out that the happy marriage of maggots and wounds has been recognized for centuries, particularly in battlefield situations such as the Civil War and World War One. Field surgeons would note that soldiers with wounds infested with maggots on the battlefield had less gangrenous tissue and less infection once they finally got to the aid station. Basically, maggots were a fortuitous contamination rather than a deliberate strategy. It required a brave psychological leap to intentionally place maggots – the symbol of a putrefying death – into wounds.

Dr. William Baer, working in the 1920s is considered the father of maggot therapy. His first efforts were successful in healing wounds, but unfortunately some of his wild maggots also transmitted tetanus, so the next step was to improve the safety profile with disinfection. Baer discovered that he could not disinfect the maggots themselves without killing them, but he could treat the eggs with a common chemical such as Lysol. He then isolated the eggs in a sterilized environment so that they would remain disinfected once they hatched into the larval maggots.

Maggot therapy then spread quickly in the 1930s. Some hospitals even housed their own insectivoriums so that they could rely on a steady supply of home-grown maggots. However, in the 1940s the discovery of antibiotics and advances in surgery doomed the maggots. The practice essentially went into hibernation until Dr. Sherman revived it in response to the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria and the growing challenge of poorly-healing wounds, particularly among diabetics. In 2004, Dr. Sherman submitted data to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that documented that maggots could actually help heal wounds. The subsequent FDA approval allowed Dr. Sherman to market his maggots as medical devices. Now physicians can order a vial of sterilized maggots, with each containing about 250 maggots, either enmeshed in a gauze pad or crawling along the sides of the bottle.

The maggots can be applied to the wound in two different ways. “Free-range” describes maggots placed directly into a wound on a piece of gauze, which is then covered with various layers to create a roof over the wound so that the maggots do not “leave the wound unescorted.” Alternatively, caged maggots are also available. Here the maggots are self contained in a dressing that eliminates any possibility of escape, but also limits the movement of the maggots within the wound. With either strategy the satiated maggots are removed after 48 to 72 hours. At this point they are the size of plump rice grains, some twenty-five times their original size.

Each vial comes with Instructions for Use, which includes the following common sense advice acknowledging the challenges of using living organisms as medical devices:

Each vial comes with Instructions for Use, which includes the following common sense advice acknowledging the challenges of using living organisms as medical devices:

• Air must be able to enter through the dressing otherwise the maggots will suffocate.

• Maggots may try to escape from the dressing when they are satiated.

• Maggots should not be used on more than one patient, nor allowed to wander away from the host.

• Escaping maggots have been known to upset the hospital staff and/or patients.

• Wounds should not be allowed to close over the maggots.

• Free range maggots are contraindicated in wounds near the anus or other body cavities.

• Maggots are contraindicated for use in the eyes.

The published studies on medical maggots are professional and dispassionate, but I can still feel the specter of the ICK factor lurking beneath the scientific discourse. The FDA meeting where maggots were approved suggests the discomfort of the panel of physicians, with the transcript noting “laughter” when coining the appropriate collective term for maggots, debating whether it should be called a herd or a swarm, and finally settling on a “muddle of maggots.” Another physician joked that the committee needed to address appropriate maggot disposal stating, “We are dealing with little animals here and we have an unusual political climate. Do you think PETA will be upset?”

From a marketing perspective, maggot laboratories have to decide how to address the psychologic ICK factor – should they ignore it, defuse it or embrace it? The promotional materials from Dr. Sherman’s Monarch lab reflect all three approaches. Much is very matter-of-fact and ignores the elephant in the room. There are also efforts to defuse the issue by defining the treatment as “maggot debridement therapy” at first mention, and then referring to it by the sanitized initials MDT so that word maggot does not need to be said out loud. This approach is reminiscent of the Viagra ads that attempt to remove the stigma of erectile dysfunction by simply calling it ED, or low testosterone that has been renamed “low-T.”

Other material from Monarch labs embraces the ICK factor, even showing affection for maggots. The free-range dressing – the one that is supposed to keep the maggots from suffocating – is trademarked “Creature Comforts.” In “how-to” videos on the Monarch website, Dr. Sherman advises the physician to put additional gauze into the wound so that the hard working “critters” have a place to take some “peaceful breaks.” Other materials take a humorous approach to the maggots. Another Monarch video shows a trio of staff members grinning as they peek into a treatment room as a dressing is being changed, too nervous to enter. The website also offers novelty gifts, including a T-shirt emblazoned with a yellow triangular highway sign saying “Caution: Maggots on Board.” Another T-shirt has a logo that plays on the milk advertising campaign: “Got Maggots – We Do.”

And then, most improbably, you can also buy minty-flavored “maggot” candy, marketed as “fun Halloween favors or treatment souvenirs.”

Monarch Labs does have one competitor, the French company BioMonde. This company has taken a totally different approach. In fact it tries to flat out ignore the ICK factor. Their website features pictures of a young boy snuggling with his grandmother, a woman who is presumably harboring several hundred maggots luxuriating in a festering wound. My feeling is that anyone in the midst of maggot therapy would either self-isolate or become a social pariah. What if one left the wound “unescorted” or became a “fugitive?” As noted by the FDA, escapées can be upsetting to the hospital staff or the patients. I shudder to think of the reaction of dinner guests or if a maggot calmly waltzed across the dinner table. Perhaps this website is suggesting a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. This strategy might work; it would never occur to me to ask a party guest if there were maggots on board.

I have now spent considerable quality time with maggots, and I am still having difficulty conjuring up a positive attitude adjustment. Conceptually, I like the idea of finding new cures in ancient practices, to get away from the bells and whistles of modern medicine. However, I just can’t shake the connection between maggots and death – the type of slow, rotting from within death suggested by weeping raw wounds, exposing tendons and even bone. Flies and maggots seem to show up promptly at the first sign of death, and I wonder if that smidge of dead tissue on my calloused heel might entice a maggot. Are we all just a maggot meal waiting to happen? Could I ever suck up the ICK factor and welcome maggots onto my body, mouth hooks and all?

Ronald Sherman notes that physicians are often more squeamish about maggots than patients, certainly understandable since maggots are typically the last ditch hope before an amputation. So Monarch Labs has pulled out all the stops with video testimonials from two patients, both of whom had to beg their physicians to get some maggots.

Steve Kozub is a very healthy and vigorous-looking 48 year-old maggot veteran who describes a harrowing experience with a botched knee replacement requiring three surgeries that left him with an infected, oozing wound. “I was languishing,” he said, “I was ready for amputation and then I heard about maggot therapy. My plastic surgeon was just playing around with my dead tissue, just removing little pieces twice a week.” After two three-day exposures to maggot therapy, his wound entirely cleared up. “I had clean, virgin, pink tissue,” he said.

While Mr. Kozub said the maggots were painless, he did admit that it was a bit disconcerting to change the dressings and see the engorged maggots squirming around and “feasting voraciously.” He gives a dramatic pause but then concludes, “Take a video camera and show people what maggots look like. Give it to you kids and grandchildren who will want to see it and have a laugh about it, but maybe wait until after Christmas dinner.” Perhaps Mr. Kozub wanted a souvenir that was more vivid than a bag of minty maggot candy.

The missing words in the following poem are anagrams (i.e. share the same letters like spot, post, stop) and the number of asterisks indicates the number of letters. Your job is to solve the missing words based on the above rules and the context of the poem. Scroll down for answers.

A wound can start out as an innocent looking ******

But it’s a problem if the skin breaks down and starts to ooze.

The surgeon couldn’t be ****** cutting away the tissue that’s dead

But when the wound doesn’t heal, the patient begs for maggots instead.

“I want something that ****** its head in my flesh and feasts until satiated,

If the maggots do their job right, then my leg won’t need to be amputated.

Answers: bruise, busier, buries (note that rubies is also a member of this set of anagrams, but I couldn’t figure out how to work it in. I suppose that the bruise could be the color of rubies…)

Follow Liza Blue on:Share: