I sat in the windowless bowels of O’Hare Airport waiting for my face-to-face Global Entry interview. Nick had urged me to sign up not because I deserved recognition as a trusted traveler, but solely to bypass TSA and immigration lines. I have objected to such elitist programs on principle – line-cutting in the grade school cafeteria was my first brush with social injustice. Now such behavior has been institutionalized for those willing to pay the $100 fee.

My interview was quick. A snoozy customs officer asked me a few perfunctory questions about my job and then casually asked me to place my hand on the digital fingerprint scanner.

I hesitated, but I had made the trip to O’Hare and had paid the fee. I set aside my aversion to line-cutting and placed my hand on the sensor. Within fifteen seconds another uneasiness set in. I imagined my fingerprints – my right-hand pointer through pinkie – winging their way across the country into the growing FBI database. I was now indelibly, inexorably, inextricably, embedded“in the system.”

Yes, the government can identify me in a variety of ways – through my social security number, driver’s license registration, and, at least on Law and Order, the detectives have easy access to my bank records, credit card purchases, and telephone calls. These are all just assigned numbers, but my fingerprints are in a totally different category. They announce my physical presence, from birth to beyond death and I had just blithely given them away – all for the sake of convenience. “The man” has me in his grasp. We are told that fingerprints are the best way to safeguard our identity, but it is also the easiest and most definitive way to reveal it. In this jittery post-Snowden society, who do I fear most – terrorists, identity thieves or my government?

I had the same queasy feeling thirty years ago, when the government required my fingerprints to work at their VA hospital. In this pre-digital era, the only record was my ink-stained tips pressed onto a flimsy card. In the sprawling VA system who could possibly want a smudgy card from a newly-minted physician? I felt sure my card would promptly get lost. Now all prints are durably digitized and stored in the FBI’s tentacled database. Originally civilian fingerprints, such as mine, were kept separate from criminal fingerprints. The FBI has merged the databases; both are searchable. In addition to the FBI, states and large cities maintain their own databases.

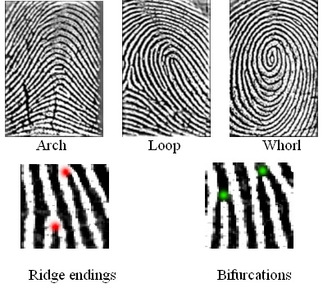

Fingerprints as a means of identity go back thousands of years. The Chinese first used them for identification as early as 200 BC. In the early 1900s US detectives started to collect and use fingerprints in criminal investigations once more sophisticated classification systems were introduced. For example, fingerprints fall into three basic patterns – loops, whorls and arches. These patterns can be used for exclusionary purposes. However, a definitive match requires further detail, based on the fingerprint’s “minutiae,” i.e. where the individual friction ridge ends, bifurcates or is an isolated island. When detectives refer to a “ten-point match” they are referring to the minutiae.

Primates (humans, apes, monkeys) and, oddly enough koala bears, are the only animals with fingerprints, which may represent the vestige of scales used for grasping. Fingerprints emerge as early as ten weeks of gestation and are fully developed, complete with minutiae, by 16 weeks – a type of research that seems both esoteric and grisly. However, genetics dictate only the presence of fingerprints, but not their specific pattern. Even the fingerprints of identical twins are distinct, an observation that escaped the editors of a recent Law and Order episode.

Embryologists have proposed a variety of environmental factor impacting the pattern, such as mechanical forces in the cramped uterus. These theories remain unproven, but the bottom line is that the multitude of factors makes two identical fingerprints statistically impossible. I imagine my origins as a fetus, my paw-like hands waving in the watery soup, skimming along the silken veil of the amniotic membrane. And all the while my friction ridges were whorling, looping, arching, and bifurcating to create the most visible testimony of my uniqueness.

It was time to spend quality moments with my fingertips. I pressed each one into an ink pad, but the resulting print was too smudgy, and I became jealous of high resolution digital images. I borrowed a botanist’s magnifying loupe and by adjusting the light and angles, I could briefly see the illusive designs. I was besotted. Elegant loops leaned left and right on index and pinkie fingers, and my ring and swear fingers featured utterly stunning whorls. Tightly compact, perfectly symmetrical, my whorled fingerprint is a pattern seen throughout nature, such as in the coils of a fiddlehead fern, the snail, the seeds of a sunflower, the curl of a centipede.

The proportions of these coils, known as Fibonaci’s golden ratio, are thought to be visually appealing and resonate with the human psyche. The golden ratio has captivated mathematicians, philosophers, biologists, architects, and artists such as Van Gogh, who painted not only sunflowers but fingerprint-like whorls in his Starry Night. I was thrilled to have my own personal golden ratio right at my fingertips.

My close-up view made my fingerprints deeply personal, but our legal system does not share my big warm and fuzzy embrace. Fingerprints are held in low regard compared to the theoretically more personal DNA sample. The “invasive” oral swab requires probable cause, judicial review, and a court order. In contrast, a fingerprint is held to vague standard of “reasonable suspicion.” No court order is necessary.

The courts have acknowledged that “reasonable suspicion” cannot be objectively defined, stating only “a reasonable person in the same circumstances could suspect that a person has been, is, or is about to be engaged in a criminal activity.” If one accepts the logical premise that the leader of the free world should set the standard for a reasonable man, well then, get ready. The discretion of police has just ballooned to an alarming degree.

Mobile fingerprinting devices now make it easier for police to act on their “reasonable suspicion.” For example, the police cannot haul someone down to the precinct for the express purpose of taking a fingerprint – this is considered an unlawful detention prohibited by the fourth amendment. Mobile fingerprinting has removed that check. Imagine a big barroom brawl. I get caught up in the melee as the police storm in and demand everyone’s fingerprint based on their squishy interpretation of reasonable suspicion. My fingerprint is whisked off to the FBI and BOOM! up pops an outstanding warrant.

The above scenario would never apply to me because I rarely go into bars, but I do feel the slippery earth trembling and shifting beneath me.

My debut Global Entry experience occurred this winter as we arrived from New Zealand. I followed the signs to an expansive bank of idle kiosks. Nick had only applied for the inferior TSA designation and so was shunted off to the general line. I felt my familiar elitist line-cutting guilt as I saw his head bobbing along the snaking line. I pressed my passport on the scanner and a light flash took a dazed gap-mouthed picture of me. Then the finger print scanner emitted a sickly green light. I hesitated. But then I thought what the hell, I’m already in the system. I put my hand on the scanner and passed through quickly. Ten minutes later Nick joined me. I had sacrificed my fingerprints for the convenience of ten measly minutes.

Iris scans and facial recognition are the next biometric technologies on the horizon. Will the courts offer them the same protection as a DNA sample, or lump them in with the humble fingerprint? Will it be probable cause or reasonable suspicion? One thing for sure, I will not willingly give them up to “the man” – I will safeguard my identity – unless of course there a convenience factor of at least thirty to forty minutes.

Follow Liza Blue on:

Share:

You might like to consider adermatoglyphia an extremely rare genetic disorder which causes a person to have no fingerprints.

This was used in a thriller book recently.

The tentacles of the state reach deep into our lives thanks to the internet and the computer. Police, the government and spying agencies can now detect, store and regurgitate data at will.

George Orwell saw a dangerous future in his novel ‘1984’, written in the late forties just before his death (he died in early 1950). In fact, he was so popular as a result of ‘Animal Farm’ that Robert Giroux pushed ahead and published an ‘Americanised’ version independently of Roger Senhouse’s copy for the English press. Consequently two different texts emerged at the beginning.

We need a new 1984 to consider, promote and advertise the reach of state agencies into our personal lives.