1960s

It was one of those in-between summers. I had outgrown sleep-away camp and wasn’t old enough to be a camp counselor, so my mother had to patch together activities to keep me occupied. Typing class was the solution.

It was one of those in-between summers. I had outgrown sleep-away camp and wasn’t old enough to be a camp counselor, so my mother had to patch together activities to keep me occupied. Typing class was the solution.

Even though I had no occasion to use a typewriter, I didn’t question the wisdom of this choice. Instinctively I knew that typing was an essential skill for a woman in the working word. In fact, my class was only girls. My mother briefly worked as a secretary before she got married. She had her own typewriter and I remember her setting it up on the kitchen table and typing out recipe cards, presumably to keep her QWERTY skills sharp. She would pull out the recipe card and gaze at it with evident pride.

I used my mother’s typewriter for the class. It was too bulky to put in the basket of my bicycle, so my mother dropped me off three mornings a week. I felt a sense of pride carrying the black typewriter in its case, imagining what it would be like to carry a briefcase filled with important papers to deliver, neatly typed, to the boss.

I liked rolling the unsullied sheet of white paper into place. The distinctive clacking of the manual keys echoed around the room. sometimes in unison as everyone practiced the same phrases. I cursed the perverse inventor of the key board. Why make my feeble left-handed pinkie in charge of the pervasive “A?” Why not swap it out with the seldom used “K,” occupying the prime spot of the middle finger of my dominant right hand?

The target was to reach 45 error-free words per minute, the threshold for the marginally adequate typist. Finding that balance between speed and accuracy emerged as another life skill, one that would have served me well when taking the SAT test in a few short years. I quickly learned it was not in my nature to take my time, go slowly and do it right the first time. My general impatience inevitably sabotaged any consistent attempt to reach the 45 WPM target. I was an obedient child, a rule follower, but typing offered a safe opportunity for risk-taking. I enjoyed the thrill of pushing the limits until the delinquent “A” would get entangled with the adjacent “S,” resulting in a smudged mess.

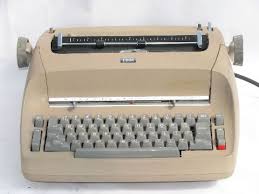

The College Years, 1970-1974

The manual typewriter segued to an IBM Selectric, a typewriter with true heft. I could hear the electric hum of progress coming from its innards, and there before me, more visible than a mother board or a whiz-bang chip, was technological ingenuity – letters rotating on a ball, eliminating any tangling of the arms.

In high school, term papers were still hand-written, but college professors expected type-written papers. This standard spawned several work-arounds for the inevitable errors. Liquid Paper was a real life-saver but required a deft touch to apply a thin veneer of white paint that could be typed over.

Thin pieces of paper dusted with dry white ink were another option to correct single letter misspellings. Both strategies required the immediate recognition of errors, since rephrasing or even changes in the length of a word were impossible. This meant all initial drafts and revisions were still hand-written. Typing the manuscript was the last thing you did, often in the early hours of the morning as the deadline loomed.

Typing was still mostly gender-specific, leading to interesting social dynamics. A girlfriend who could type was a real asset to a “hunt and peck” boyfriend with limited typing skills. From the girl’s point of view, typing a boyfriend’s paper into the night demonstrated loyalty and commitment. The boyfriend might respond by assigning her a coveted drawer in his dorm room where she could store her clothes. A boy without a typing girlfriend was shit-out-of-luck, resulting in ill-considered relationships.

This dynamic was not without risk. A hack job could scuttle a romance. I bungled the references in one paper I typed for a boyfriend. This error was beyond anything Liquid Paper could rectify, though in my defense the reference style was not clear in the draft I was handed at 2 AM. The references had to be hand written in. The relationship barely survived.

Summer Job, 1975

Ideally, one would like to have scintillating and intellectually stimulating summer jobs that leave you enthused about the working world and post-college prospects. Not so the summer of 1975 when I had a job in a botanic garden stamping metallic tags for trees. Words per minute were not a job qualification since I had to bang down on the keys one by one. The sound was metallic, dissonant, rasping, brutal.

Forget about using my pinkie for the letter A. Only my two index fingers were strong enough to press down the keys. Each day my typing assignment consisted of a list of the trees arriving from a nursery. I might arrive to find a list of 235 individual tags for Prunus padus, 215 for Quercus alba, or 135 for the more challenging Viburnum prunifolium. All day long I sat at the stamping machine in a stifling airless garage. The machine blew hot air up my mini skit leaving tender thighs exposed to the hot metal chair.

This miserable job was inspiring in a way. It lit a small lamp of feminism. I was never going to accept typing as women’s work, nor would I ever type for anyone else again. Men were on their own.

Working World, 1984 -1990

After college, I went to medical school followed by a pathology residency. My entire medical school education consisted of scattershot multiple-choice questions, first a question on hematology, then perhaps cardiology, followed by some bizarre weeping skin disease. All I had to do was fill in little bubbles on the answer sheet and pray I didn’t get them misaligned. I didn’t type for eight years.

After my training, I went to work for the American Medical Association, writing reports on new medical technologies. Still I didn’t have to type. Secretaries were on call to type my handwritten drafts using an early version of a word processor. I would receive the first typed draft, make handwritten revisions, return the document to the secretary for multiple rounds of revisions.

I felt ashamed asking another woman to type my work. It was also an inefficient system. Inevitably, the well-meaning secretary would introduce new errors while correcting old ones. It was far quicker to do my own damn typing, and I was grateful for those long-ago lessons on the manual typewriter. I became a fine typist.

Current Day

I have been firmly ensconced in the word processing world for 25 years. The deliberate clacking sound of the typewriter has evaporated, replaced by a softer, almost murmuring click of a keyboard as my fingers race across the keys with abandon. A balance between speed with accuracy is unnecessary. I imagine an invisible minion scurrying behind me, tidying my impetuous errors. The evolution of my typing has reached a resting point, at least until I get an iPad and devolve into a silent and tactileless word of hunting and pecking.

I cannot imagine creating a hand-written first draft, and I wonder how word processing has changed the way I think. Before I had to carefully organize my thoughts, perhaps write up an outline. Now I can just barf up anything on the screen and work my way into the essay. The handwritten first draft may have squelched creative barf blasts, but the flexibility of the word processor might be dampening a more deliberate process. I no longer have to turn my ideas over and over before committing them to paper, polishing their rough edges like a smooth stone. Ernest Hemingway wrote out his first drafts in pencil commenting, “Wearing down seven #2 pencils is a good day’s work.”

I shudder at the new standard of perfection. Typos are no longer tolerated. I have spent hours searching for the last rogue typo, and then start the search again in case I have introduced a new one. Submitting a story for publication demands a slavish devotion to format. Any slight deviation can result in a fatal ding by an editor who is looking for an easy reason to reject something by the second paragraph. To me, that is like rejecting a cake with tilted tiers and uneven frosting (as mine always are) without tasting it. Typing for a punitive taskmaster is a tyrannical process that can suck the life out of creativity.

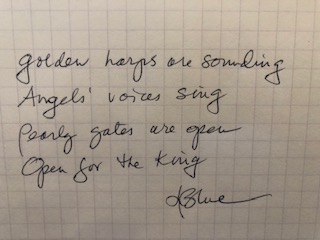

I regret that word processing has usurped the fine art of penmanship. My class eagerly awaited third grade when we learned grown-up cursive. I was proud of my grade A efforts. Opportunities for any handwriting are now minimal, limited to grocery lists, thank-you notes and condolence letters. My pencil sharpener sits idle on the back counter. I miss my handwriting, readable and beautiful. I particularly like the way I make the loops of my below-the-line letters – my lower case g’s and y’s and are peppy and confident.

I still recognize my father’s careful and cramped writing filled with his unique misspelling of the word “stuff” as “stough.” My mother’s writing was loopy and fluid as if she was in a rush. Both styles reflected their personalities. I regret my children do not have many occasions to reflect on how my handwriting defines me.

My children grew up in the era of word-processing. They never had to hand-write a first draft, nor navigate the gender politics of college typing. Word processing was just handed to them as if it always existed. Just as I cannot believe that my parents grew up without TV, my children cannot believe I grew up without a TV clicker, nor can they believe that Liquid Paper was a coveted item at 3 AM.

Follow Liza Blue on:Share:

Brings me back a few years. A year of typing classes in high school all paid off with the advent of using computers at work. My iPad has forced me back into hunt and peck. Oh well.

Ha! I don’t have an iPad, so I have not devolved to hunting and pecking.