An unexpected change in summer vacation plans left me with a solo week of unstructured time. Although I have become quite skilled in puttering and frittering, I didn’t want to fall into the abyss of bad TV, cheap novels and cookie dough. I committed myself to a week of purpose and accomplishment. YouTube tutorials would provide my structure. I vowed to learn a new skill each day.

I sought nominations from family and friends. My five-year-old grandson suggested I learn how to climb a tree. YouTube is well stocked with tutorials on tree climbing, offering such practical advice as “check the rope before you start climbing.” While tempting, I have recognized that the full flower of my nimble childhood has long since wilted. Any activity involving gravity now requires a well-appointed and manned safety net. I decided to focus my attention on activities that could draw on my transferable skills. Possibilities included juggling (good hand/eye coordination), cake decorating (fond of chocolate), crossword construction (I do New York Times crossword every morning) and taxidermy.

A tutorial on taxidermy could revive my dormant dissection and autopsy skills honed as a pathologist. Additionally, we spend our summers in the hunting environment of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where houses are adorned with mounted fish and deer. I didn’t want to deal with slimy fish, and a deer was too big. Mice are abundantly available in our house – the snap of a mousetrap is a familiar sound – but they are too small. A squirrel or a chipmunk emerged as the target size. Nicely taxidermied, they could make a cute addition to the fireplace mantle.

“How to Taxidermy a “Squirrel” popped up on YouTube, featuring three cheerful millennials working with road-killed squirrels. The prospect of scavenging roadkill was not personally appealing and would not be a good look for our new neighbors. I happily embraced the traditional gender roles of hunter-gatherers. I asked my husband Nick to forage me a specimen. His first target was the chipmunk trapped in our garage. He hoisted the pellet gun and fired away, leaving the walls pock-marked but no chipmunk. Chastened by his failure, he stopped to chat with the neighbor as he walked the dog. Russ asked about his plans for the beautiful day. Nick could have said that he was going fishing, an entirely reasonable and appropriate plan, but instead he chose to mention that I was in the midst of my YouTube Skills week and was planning to study cake decorating and taxidermy. What a stroke of luck. The neighbor said a squirrel raiding his bird seed had just that morning succumbed to acute lead poisoning, i.e., he’d shot him. Nick returned home, triumphant as he handed me a large black squirrel in a plastic bag.

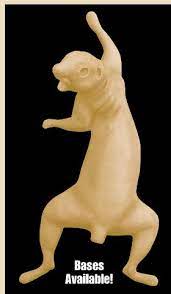

I delved into the world of taxidermy and learned that this art has been simplified over recent decades. Traditional taxidermy required elaborate wiring using native bones to create poses. Plastic molds of squirrels are now available – running up or down a tree, eating a nut, and a pouncing pose with the squirrel standing on its hind legs. The skinned hide can be fitted over the mold and discreetly sewn up along its belly. Accurate plastic eyes in different sizes are an important accessory. Note: squirrels have an oval pupil.

Many YouTube videos detail the process of skinning the animal. Some specifically focus on taxidermy, others target hunters who plan to eat the squirrel. Regardless, with a few deft cuts you can essentially turn the squirrel’s skin inside out – at least you can on YouTube. My initial efforts were frankly hack jobs. I trolled through other tutorials and came to the reluctant (but convenient) conclusion that I did not have the right equipment. My husband’s fishing filet knife was too big, the regular scissors were too big, the fingernail scissors too small. A scalpel would have helped. I had not appreciated the several week process of tanning the hide, which would require a $100+ investment for a kit from Amazon.

Apparently, taxidermy is not suitable for the casual hobbyist. However, my squirrel deserved better than a routine disposal in the garbage bin. I wanted a positive learning experience, not discovering what I was no good at. I refocused my efforts on gut dissection. Guts hold no interest for the taxidermist or hunter. They are nothing more than disposable byproduct or inedible offal. For a pathologist, guts are the meat and potatoes of autopsies and surgical biopsies.

I carefully opened up the squirrel’s rib cage and abdomen. I was stunned. My squirrel had the most lovely and dainty organs. The central heart, surrounded by two frothy and pink lungs, the large liver overlapping the stomach (incidentally stuffed with digested bird seed), the slinky intestinal coils and the paired kidneys. I even found two adorable testicles tucked away in the groin. To my jaded pathology eyes, these organs were fresh and innocent, untouched by disease. The lungs were not streaked with sooty pollution, the human equivalent of an ashtray, the liver was smooth and glistening, not studded with cirrhosis as I have seen so many times.

The array of the organs was identical to a human, a miniaturized version of my own. An anatomy professor once told me that he found entrails boring as they were the same across all mammals. His interest was translating the alignment of bones and muscles to their function. The consistency of the guts was the reason I found them fascinating. With a few tweaks here and there, this design has been conserved throughout all mammals, bypassing natural selection. It was perfect the way it was.

As a thought exercise, imagine an intelligent designer tasked with developing mammals’ engine room. (This is just a hypothetical and convenient thought exercise. There is no such thing as an intelligent designer. Just go with the concept for a moment.) The designer thinks “I need a pump filled with blood and then a way to exchange gases.” She notices how the successive branching of limbs and leaves expand the surface area for gas exchange. Inspired, she applies the same principle to the lungs, creating air fills sac with small blebs. These are the alveoli. Processing food and waste was the next challenge. She designs the liver and kidneys to serve as filters and garbage disposal, the stomach and intestine absorb food. Her plan works perfectly.

I imagine the designer handing over blueprint to the captain of evolution and saying, “Go to town. Unleash your imagination. You can change the skeleton and musculature to fit all niches, longer legs for the springers, short legs to the diggers, sharp nails for climbing, strong flat teeth for chewing herbivores, sharp teeth for the carnivores. Play with sight, smell and hearing. But don’t touch the guts. I have nailed the entrails. Even better my design is scalable. You can make the heart or anything else big enough for a whale, or tiny for a mouse. My job is done. Grind away, evolution, take it from here. There’s no rush. Take all the time you need.”

Follow Liza Blue on:Share: