YouTube Skills Week: Juggling

Juggling seemed like an achievable parlor trick as part of my YouTube skills week. I have reveled in the success of my other trick, a loud, piercing whistle with my thumb and index finger placed on my tongue, enough to call a cab or find my husband who has vanished into the depths of Costco. The reaction is one of envy, “Boy I wish I could do that.” Juggling would expand my repertoire. After a quick demo I might hand juggling balls to my awestruck audience, tell them it is easy and then watch in mock astonishment when, flummoxed, they hand the balls back to me with a dispirited shake of the head.

Hand-eye coordination must be the bedrock of juggling and I have great confidence that I have the necessary skills. Any of my success in athletics is based on my hand-eye coordination. I am a notoriously slow-moving object, but I can step up and fire a blazing tennis forehand down the line or cross court. In baseball, I can go with the pitch and hit to the opposite field. And I will seize any opportunity to relive a glorious save in my brief human target career as a hockey goalie on a senior women’s team. My opponent wound up at the point and let fly a fierce slap shot. My left hand shot up and I felt the stinging snap of the puck in the glove. Players on both sides stopped play and tapped the ice in recognition. A tour-de-force of hand eye coordination.

Despite my impressive credentials, previous YouTube Skills exercises have taught me the importance of managing expectations. I do not aspire to be a circus performer, an entertainer on cruise ships or at the local county fair, and I do not anticipate juggling flaming torches or machetes.

My only goal is to complete a single flash, juggling jargon for a simple three ball exchange.

Really how hard can juggling be?

There is no shortage of juggling tutorials on YouTube. I pick Josh Horton, a professional juggler who has won nine gold medals, has 16 Guiness records and endorses his own line of juggling balls – small millet-filled balls that snug into your palm and don’t bounce when you drop them. Tennis balls are not recommended for this reason. The ball needs to make a comforting thud when it hits the ground.

I start by throwing a single ball from one hand to another, my feet one yard apart, my shoulders squared up, my elbows at 90 degrees, my hands at my waist. No problem. The degree of difficulty rises when I move to two balls. My hand-eye coordination may be excellent for a single moving ball, but falters at two balls. Josh explains that you cannot look at an individual ball. You must stare straight ahead and use your peripheral vision to get a sense of the movement.

Muscle memory emerges as a critical skill. The timing and the ball throw must be exquisitely consistent. With enough practice, muscle memory must lock in and it all comes together in a grateful AHA! moment.

This moment remains elusive.

My ongoing failure gives me time to ponder the evolution of hand-eye coordination. Is this one of the skills that has propelled primates to the top of the heap, and specifically humans to world domination? Forget about juggling, hand-eye coordination is required for the simplest task, reaching for that raspberry that has rolled off my toast and fallen to the floor, as is its custom, with the associated threat of being smooshed into a stubborn red stain on the wooden floor. This task is a mastery of coordination, not only the hand-eye part, but the tactile input of feeling the delicate raspberry with my nifty opposable thumb.

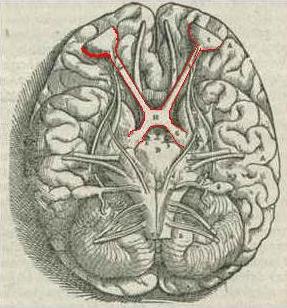

Hand-eye coordination hinges on how visual information is presented to the brain for interpretation. In vertebrates, the optic nerve from each eye crisscrosses the midline in a structure at the base of the skull called the optic chiasm, so most of the input from the left visual field, for example, tracks to the right side of the brain.

In primates and other predators, the eyes are frontward facing creating overlapping visual fields. In contrast, prey animals, such as rabbits, have eyes situated on the sides of their head. They rely more on their peripheral vision to scout for predators. Their fields of vision don’t overlap to the same extent as humans.

The big innovation in primates is the organization of the optic chiasm. A greater proportion of visual nerve fibers stay on the same side and do not cross the midline. Therefore, each side of the brain receives input from both eyes at the same time. This arrangement results in greater depth perception, binocular vision, and vital hand-eye coordination.

Picking up a raspberry can be done at leisure, but juggling is a time-critical task. Simultaneous input from both visual fields is a critical time-saver. For example, the visual input doesn’t have to undergo another neural connection to the other side of the brain. The practical consequence is not only speed but a reduction in the number of neurons needed, and thus the size of the brain. Matz Larsson, a Swedish researcher, estimates that without this economical architecture, the human brain would have to be 12 miles wide. (Yes, I checked this statistic several times. Larsson’s article is dense and tough reading, but the statistic is based on the brain size if each neuron were connected to all other neurons, as might be the case in a very simple brain with a limited number of neurons. So clearly this statistic is provided for dramatic effect, but you see the point. The human brain is a model of speed and efficiency.)

I practice juggling every day, hopeful that muscle memory will be seared into my brain. Wayward balls keep thunking at my feet or I fling them off sideways. However, at my watershed senior age of 70, I am newly comfortable in admitting that I lack the commitment to be a juggler.

It’s not going to happen.

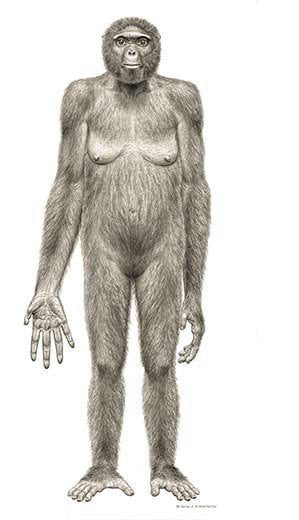

But this exercise in futility does have its charms. I think of Ooga Magook, our common early hominid ancestor, who realizes that he is a skosh more agile than his peers. He can climb up and down trees with ease, he throws his spear with great accuracy. He doesn’t realize that he has been blessed with the mutation for rogue neurons that have established a more efficient pathway, that he is the unexpected recipient of superior hand-eye coordination. Ooga is a popular mate and sires dozens of children, who do the same over thousands of generations. Once again, I am in awe of the grinding elegance of evolution down to the smallest detail, and I am grateful that my brain is not twelve miles wide.

Follow Liza Blue on:Share:

OUTstanding choice for a skill to learn via YouTube this time around. What an effort to be commended!