Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

How YouTube can put purpose into an unstructured week.

Follow Liza Blue on:Share:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

How YouTube can put purpose into an unstructured week.

Follow Liza Blue on:Fifty years of solving the NY Times Crossword puzzles have blessed me with a peculiar vocabulary, but I also revel in their creative themes and clues. I settle in for Sunday breakfast, open the Times magazine and wonder how long it will take me to unlock the theme, obliquely hinted at by the title. One memorable crossword was titled E-Land, and halfway through I realized that “E” was the only vowel used in the entire puzzle – over two hundred different words. What a satisfying moment, one that left me in awe of the constructor who could pull off such a feat. The clues themselves often involve clever misdirection or puns. I have learned to spot heteronyms (words spelled the same but pronounced differently) like wind, which may be either a breeze or what you do with a ball of wool. The crossword puzzle offers a glimpse into human creativity, accessible every week at the kitchen table.

On June 22, 2022, clue 25A described a four-letter word as a “Body part that humans have that other primates don’t.” I have a working knowledge of comparative anatomy dating to my college days as a zoology major but struggled to imagine the solution. Sometimes the crossword answer involves a “rebus,” where more than one letter fits into a square. There was no way to compress “opposable thumbs,” “fingerprint,” or “bipedal gait” into four letters. This clue was entirely intriguing. By solving the intersecting words, I determined that the answer was CH–. And then I got the other two letters. The solution was “chin.”

I wondered, “Certainly apes have chins, don’t they? How could a chin be ours alone?”

One of the honor codes among my brethren is to swear off the internet as a crossword lifeline, but there is no shame in investigating a provocative clue. The human chin called to me. Sometimes you inadvertently stumble into a rabbit hole, but I jumped at the chance to dive into the wonder of the mundane chin.

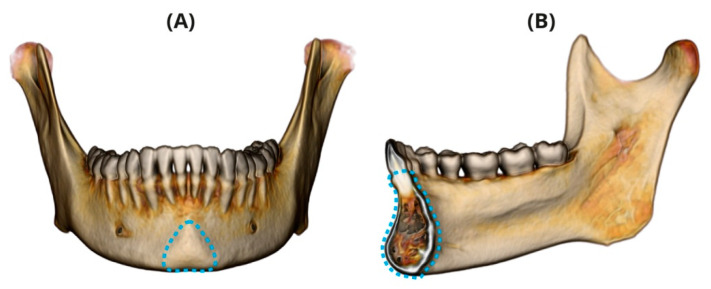

My first assumption – that the chin is merely that portion of the jaw directly below the mouth – is wrong. No, the chin, technically called the mentum osseum, refers to the small wedge-shaped bone located at the midline where the two halves of the jaw fuse during fetal development. The base of the triangle is created by “paired bulbous formations on either side of its inferior margin.” These formations determine the shape of the chin, indicated by the dotted blue lines in the figures below.

The key to the crossword puzzle clue, i.e., the unique human body part, is that we are the only animal whose chin extends beyond the teeth. In fact, the chin is a defining skeletal feature of modern man.

From an anatomic point of view that little nubbin that barely protrudes beyond the canines is what makes us modern humans. Our chin puts the sapiens into our homo.

I thought of my posthumous mentor, Charles Darwin, the great noticer of the natural world. His famous Galapagos finches are utterly bland birds to incurious eyes. Darwin noticed the small variations in their beak structure that predicted their function as seed or insect eaters. These beaks formed the crux of his theory of natural selection.

The uniqueness of the human chin would have fascinated Darwin. He would have searched for intermediate chins to illustrate their evolution, and then speculated on the function of the chin. However, the skeletal remains of early humans were incomplete during his lifetime. Darwin was aware of the first Neanderthal skull discovered in 1856, but only commented that the skull represented an early human. His lack of apparent interest in the chin can be excused since the prominent orbital ridges of the Neanderthal overshadowed the humble chin. Besides the first Neanderthal skull was missing the lower jawbone.

I imagined how Darwin would investigate. I considered his basic approaches: 1) the human chin provided a natural selection survival advantage, consistent with his 1859 book The Origin of the Species; or 2) the size and shape of the human chin plays a factor in mate choice. Darwin addressed sexual selection in his 1871 follow-up book, The Descent of Man.

An internet search revealed a lively and ongoing debate about the human chin along these Darwinian lines. There have been many studies of the mechanical stresses of our chewing or our unique form of speech that could have resulted in the natural selection of the human chin. This research did not produce compelling results. Others scientists suggested that the chin is an unintended consequence, genetically linked to a critical, but as yet unknown, survival advantage. We share 95% of our DNA with chimpanzees. Somewhere in the remaining 5% is the secret sauce that has propelled us to our dizzying apex – with the chin as a byproduct. This remains only a theory.

Slim data does support the chin as a factor in mate choice. The basic premise of this theory is that chin shape should differ between males and females. Two enterprising anthropologists used sophisticated CT scan analysis to compare chin shape in museum collections of human skulls. They found small but distinct differences in chin shape between sexes.

The data is not overwhelming but it does support an aesthetic role of the chin that is not shared by other primates. Certainly chin shape is a frequent topic in the popular press – square, pointed, strong, weak, chiseled, dimpled. (A dimpled chin results when the jawbone fails to fuse and the skin sags into the resulting gap.) However, the exact contribution to sex appeal remains elusive. Based on the strong American embrace of the concept of “more is better,” Jay Leno would be considered the sexiest man alive, the alpha male. Many would disagree with this designation, probably even his mother. .

If we assume the converse, “less is less,” Mitch O’Connell might be at the other end of the spectrum, His weak chin, accentuated by flabby neck skin, might place him in the running for the ugliest man in America, a designation many might agree with.

My detour into the mundane chin has salvaged my sense of wonder, which had taken a dark turn. I wonder about the casual and deliberate cruelty of Americans, I wonder how an oversized American flag has coopted its identity of unity to a symbol of divisive and uncompromising political beliefs, I wonder when the COVID pandemic will end, and I wonder about the dimming prospects of our planet. It is a dispiriting exercise.

Rabbit holes provide a more deft solution. I cradle my chin in my hand as I wonder at the breadth of human curiosity at work. I see the footprints of Darwin, I see people whose careers are built off the chin, I see the chin pushing the frontiers of CT analysis. I am thankful for the Crossword puzzle clue that has ushered me back to the pleasure of wonder.

Follow Liza Blue on:Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The human chin is the defining anatomical feature of modern humans

Follow Liza Blue on:Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The defining identity of a loud whistle.

Follow Liza Blue on:I grew up in a gender-neutral household, the only daughter with five brothers. You might have thought my mother would have doted on her only daughter, but she never singled me out with any advice on what it meant to be feminine. She never said to me, “Oh, you look so cute in that dress, let’s put a bow in your hair.” I don’t recall watching her get dressed for a party, gazing in the mirror, patting her hair, daubing on make-up, discussing which dress and shoes to wear. She would scrape a comb across her hair, take a quick look in the mirror, grab her purse and she was ready to go. The purse only contained nail file and a tube of ChapStick – so distinct from the bulging purses of other mothers. I could understand the ChapStick but the nail file mystified me. What fingernail emergencies could occur at a dinner party? She told me that it had been there for years and she figured she might as well leave it there.

Other mothers might refer to the “beauty parlor.” My mother called it the “beauty store,” as if beauty was not innate, it was a commodity that could be purchased. She only went to the beauty store for haircuts, never perms or dye jobs. This was in the 1960’s when Clairol’s slogan was “Only your hairdresser knows for sure,” when the dark roots would be a social catastrophe. She told me, “Once you fall into that dye pot, you’ll never get out.” I had seen TV moms, June Cleaver among them, and maybe Donna Reed. They looked nothing like my mother.

My mother’s identity was based on sports. She taught all her children how to ice skate and ski, play tennis (her favorite sport), how to throw a spiral football, and baseball, including its arcane rules. These were the activities that were interesting to her. I followed her lead. At age eight, I could recite the infield fly rule, a balk, and dropped third strike. In later years I discovered that the ability to talk sports with men was a social asset. I wonder whether she thought the same.

Music and word play were her other great talents. She often arrived at a party with her guitar ready to serenade the hosts with a tailor-made ditty. I never heard my father say, “Fan you look lovely tonight.” He mostly felt anxious that my mother might embarrass him with her clever and irreverent humor. As a preteen I asked her what the word “sexy” meant. She told me that a sexy woman was funny and could make men laugh.

With no other social cues from older sisters or aunts, my looks, whatever they might be, didn’t become part of my identity. My routine was the same as my mother’s. I only looked into the mirror for a perfunctory comb and quick check to ensure a straight part. As a kindergartner, I could wear pants, but in middle school, girls had to wear skirts or jumpers, oxford shoes and bobby socks. I rotated a small stable of outfits, but I never cared what I was wearing on any given day, never expecting, or receiving, any comment on my physical appearance. I was a good student and a decent athlete, which was enough.

I began to sense a few cracks, a growing realization that looks did count for a bit of something. It sounded like a joke when she told me that people said she looked like Ingrid Bergman and my father looked like the 1950s heartthrob Tab Hunter. I had no idea who the actress was but assumed that all movie stars must be beautiful. There was pride in her voice, implying that she was pretty enough to land a heart throb as a husband. A few days ago, I was sifting through some family albums and found a picture of the two of them taken at their 1950 wedding.

Well, there it is. Yes, I can see it now. Wow. Who knew?

But these glamour shots are not my memory of my mother, which took shape in the 1960s after she had six children in ten years, when the beauty parlor became the beauty store, and getting six children fed and clothed was a consuming challenge. I’m guessing that any pride in her looks were superseded her maintenance-free identity as a witty and clever woman, an athlete and a musician. One day she came home from the grocery store and announced that Debbie had “let herself go.” She told me Debbie was no longer one of the town’s beauties. I sensed her delight that her identity as an accomplished and interesting woman was timeless. Beauty was ephemeral.

My suburban grade school was utterly homogeneous, white, Christian, affluent. I had no tools to evaluate my classmates’ looks, particularly since everyone looked similar and wore the same range of clothes. Some were taller, some had blond or brown hair (one red head was an outlier), but beyond that I was clueless. Sure, I realized that there was a spectrum, with knock ‘em dead movie star looks stretching off to the right and presumably a circus-grade ugly look on the left. I had heard whispers that Lisa was the prettiest girl in our grade, but I had no idea why. Maybe her thick blond hair pushed her a smidge to the right on the spectrum, but as far as I could tell everyone clustered at the mid-point with minimal deviation.

This was my status at age 10 or 11, when I arrived at Hillaway, my first sleep away camp.

My bunkmate Nancy was unhappy with her assignment in our cabin. She was a returning camper, a few months older than the rest of us, desperate to be in the “Old Timers” cabin, a more prestigious cabin in a plum location on the way to the horse barn. As I looked at Nancy sitting cross-legged in her top bunk, the spectrum of looks crystallized into sharp focus. Nancy did not cluster in the middle, well beyond a smidge. I distinctly remember her angular face, pocky complexion and most particularly her sharp nose and cavernous nostrils. I did not know why Lisa was said to be pretty, but all on my own I could figure out that Nancy was, let’s face it, far off to the left. She did have a singular talent – her whistle, a loud, piercing whistle that carried across the lake. I thought, maybe she looks at herself in the mirror and thinks “I might not be the most beautiful person in the world, but my whistle makes up for that. I am special. I am an individual.”

I wanted that whistle. The entire cabin of girls wanted that whistle, wanted to be as unique as Nancy. I imitated her technique, putting my thumb and index finger in a semi-circle on my tongue. I blew until overcome with dizziness. I slid my fingers around my tongue, adjusted the fold of my tongue and then different combinations of fingers. I was ready to give up. And then it happened. A loud piercing whistle erupted with such force that it threw me back on the bed. Its horsepower, timbre, and general greatness far surpassed Nancy’s. My whistle reverberated through the cabin and ripped across the lake. The other campers cheered. Nancy sulked. She no longer had sole possession of her special gift. I had stolen it.

That whistle remains a signature part of my identity. I have used it at sporting events, to hail cabs, to find someone in the Costco parking lot and is the best thing to come out of Hillaway camp. The rest of camp was forgettable, I hated horseback riding, sucked at archery, and didn’t pass the swim test and wasn’t allowed to swim out to the raft. It was worth every penny. I still get compliments on my whistle. .

When I got home, my mother immediately recognized the whistle’s importance. She was jealous. I tried to teach it to her for the next 65 years, but she never mastered it.

Follow Liza Blue on:Marketing Unplugged: Pot Pourri, Volume 2

Toothpicks

I was surprised that the grocery store offered such a variety of toothpicks. I was experimenting with tater tots as a provocative appetizer at my grazing cocktail party, one of those affairs where if you stay focused and deliberate you can cobble together a decent dinner. The idea was to upgrade the tots with a medley of sauces, not pedestrian catsup, but catsup with rosemary and garlic mixed in, an aioli sauce, or some sort of chutney. However, tater tots tend to be a bit greasy, hence the need for toothpicks.

I estimated that I needed about 50 toothpicks, but each option included at least 250, so I figured I’d be investing in a lifetime supply, all for the low, low price of $2.50. I nixed the multicolored toothpicks due to their polluting dyes. The eco-friendly bamboo toothpicks were too fancy. A contrived curlicue at the top was too frou-frou for my humble tater tots.

I also eliminated ones topped with a plastic frill. These frequently adorn a club sandwich where they emphasize the heft of the multiple layers,and suggest that wide open jaws may be inadequate to accommodate the sandwich without squirting mayonnaise and tomato juice. I recalled an incident when I misaligned my bite and sent the toothpick up my nostril, now reminiscent of home COVID test.

The double pointed ones seemed better suited to oral hygiene. On a final impulse I reached for the jar of “Best Choice Elegant Toothpicks,” whose modest notches at the top earned them the title “elegant.” These toothpicks would elevate my tater tots . Any other flourish would be pretentious mocking of my tots.

When I got home, I studied the labeling more closely, an entertaining exercise that I heartily recommend (alternatively evidence that you have a serious case of not enough to do). The toothpicks are 100% Guaranteed. Guaranteed for what? What sort of actionable mishap could befall a toothpick? Perhaps the label should note that toothpicks are not suitable for small children. If I counted them, would I discover that they had shorted me a couple of toothpicks? In smaller print, the label notes that the toothpicks are “Made in China.” I imagine that the limited demand for toothpicks meant that these had languished on the shelf for years; our nation’s toothpick supply has not been gutted by supply chain issues.

My party tots were a big hit.

Airline Snacks

A recent airline upgrade qualified us for two snack bars. A packaging of a blueberry and pistachio bar claimed, “This Saves Lives.”

I tend to interpret things very literally, so my first thought was that I was saving my own life by eating the bar, that somehow at that very moment my life hung in the balance. The marketing on the back of the package was reassuring. “Buy a Bar, Feed a Child. For every bar bought, a bar is donated to a malnourished child.” The movie actress Kristen Bell is a celebrity endorser who states, “It makes me feel good when I lay my head on a pillow at night that I could be of service to someone else.” However, I did not buy the bar, the airline did, so will I feel better when I put my head to pillow? I’m not saving any lives; I am the collateral beneficiary of the airline’s marketing decision. Am I supposed to think better of the airline or should I be motivated to buy my own stash of bars? Probably both.

The second snack bar was called, “That’s It.” I had recently celebrated my 70th birthday and was feeling the pinch of mortality. The name sounded ominous. In addition, an airplane comes with its own anxiety issues. I thought of the death knell phrase “that’s all she done wrote.” I prepared myself for a jolt of turbulence followed by a dangling orange air mask. With grateful thanks I realized “That’s It” referred to the limited number of ingredients in the snack, just apples and bananas, nothing more.

Spirit Elephant Menu

I was excited to try the “Spirit Elephant,” a well-received vegetarian restaurant in a nearby suburb.

“At Spirit Elephant, we elevate and showcase local and seasonal vegetables through a globally-influenced, approachable menu in a beautiful space. We are proud that every bite of our flavorful food is kind to the planet and all beings on it.”

I typically order the vegetarian entrée at any restaurant, reasoning that these entrees require more creativity – the chef can’t rely on an impressive slab of meat to speak for itself. A dedicated vegetarian restaurant must be even more creative to entice skeptical carnivores.

But I had their marketing strategy all wrong. The menu did not try to lure in carnivores, it tried to make them believe that they were eating meat by disguising the vegetables. The menu included “Chicken Ceasar Salad” and “Calamari Fritti.” Photos of these faux dishes were proudly displayed on their website.

When I inquired about the provenance of the “calamari,” the waiter told me that oyster mushrooms were standing in for the calamari. The chicken in the salad was a “Beyond Chicken” plant-based alternative. When my “calamari” arrived it tasted like deep fried oysters, so why not call them that? I imagined a restaurant consultant advising the Spirit Elephant, “the ladies will bring in their men for dinner, but once they’ve got their asses in seats, you’ve got to throw those men a bone, give them something they can identify with.”

I also wondered about the legality of calling something “chicken” when it isn’t. Chicken has such a solid identity that the FDA and the Federal Trade Commission have not seen fit to regulate the name. When consumers see chicken on a label, they don’t question what it is. Other commodities such as chocolate or jam have to conform to a mandated definition. The only corollary I can think of is the FDA definition of “imitation crab meat” as a specific entity. Consumers might know that they are not eating crabmeat, even though it is manufactured to look and taste like crab meat. I have spotted creative labeling in the grocery store, where “chicken” is deceptively misspelled as “chick’n” to avoid criticism that their product is mislabeled. To their credit, the Beyond Chicken product clearly identifies their product as “plant-based chicken.” However, the day may come when the FDA has to devise a regulated definition of the familiar barnyard chicken.

Better Than It Has to Be

“Better Than It Has to Be” is not an endorsement that prompts me to stop in at Coburg’s for a milkshake. Better than what? Is it better than the competitor down the street or better than the lackluster health department doing a cursory search for scuttling cockroaches? The car rental company Avis successfully used the comparator “We Try Harder” as it battled against the leader Hertz. Avis embraced their identity as the gritty number two, implying that their work ethic was better than the smug behemoth Hertz. One key difference between cars and restaurants is that cars are a commodity, while milkshakes and ice cream are not. My husband is a fan of milkshakes, and he clearly knows that the shakes at Culver’s or Dairy Queen are better than other fast-food joints.

I suggest that Coburg adopt another time-honored marketing strategy. Go for equivalence along the lines of “Nobody does it better.” Instead of comparing yourself to the lowest common denominator, compare yourself to the top. You’re not saying you’re the best, you’re just saying that you’re among the best.

Best By/Sell By/Use By Dates

When our adult children forage in our refrigerator and pantry, they meticulously check the best/sell/use by dates. Their eyes roll as they discard vintage items. Our approach is more casual, relying on sight and smell. The container of sour cream often migrates to the back of the fridge, and when rediscovered, I am never surprised by its rainbow of fuzzy mold. Milk can be assessed with a sniff. A Consumer Report publication is reassuring. “Spoiled food will usually look different in texture and color, smell unpleasant and taste bad before it becomes unsafe to eat.”

Our children think that expiration dates are there for a reason and that we are being careless with our health and safety. Not so. The FDA does not mandate these labels. These are marketing terms developed by the manufacturer, which immediately makes me suspicious of a hidden agenda, i.e. a hair trigger to throw away perfectly good food. A report from the National Resources Defense Council notes, “In the United States, more than 80 percent of consumers report that they discard food prematurely due to confusion over expiration dates.”

Here is the Consumer Reports rundown on the marketing terms,. With the single exception of baby formula, none involve safety.

Best by date: This date guarantees the period of time the product will be at its best flavor. It is not about food safety, but about taste.

Sell by date: This date is determined by producers to inform sellers when to remove items from the shelves. Items can last for several days to weeks past this day.

Use by date: This is the last day the producer guarantees the best quality of the product. With the exception of infant formula, this is not a safety date nor a mandatory label.

Recently I made a salad recipe that included slivered almonds. I rummaged around the crowded pantry until I found an opened pack lurking at the back of the drawer. The almonds looked fine, smelled and tasted okay. The salad was a success. Afterward I noticed that the “use by” date was 2017, five years ago!

Follow Liza Blue on:Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

The intracacies of toothpicks, airline food, fake chicken, fast food signage and sell by dates.

Follow Liza Blue on:I sit in the leather chair, feet outstretched on the ottoman, pillow on my stomach, book resting on top of that. I have a very limited view of myself, basically my hands and the outline of my feet inside a pair of socks. This is a welcome change from Zoom calls where the time spent looking at my image has surpassed the cumulative time in front of a mirror. I’m tired of dwelling on the emerging dewlap on my neck, a structure commonly seen in hoofed mammals, lizards, and 70-year-old humans.

The ottoman is weathered with crisscrossing scratches and dings, but it is an inviting look. The same lived-in look on upholstery – tattered, frayed – would call for a freshened, upgraded makeover. I share a serene sense of identity with my ottoman.

I look at my hands and realize that if I hyperextend my wrist, my lax skin is thrown up into folds that look like a mountain range from the beginning of time. As I slowly clench my fist, the skin tautens, the wrinkles disappear, and a flat plain of smooth skin emerges, like an unruffled desert I practice simulating the millennia of erosion and imagine the dinosaur era, from the Mesozoic through Cretaceous period when an asteroid wiped them all out.

A distinct memory from my 45th birthday burbles up – the moment I realized my life was surely half over. This did not prompt thoughts of how to ennoble my remaining time. I was completely consumed with the responsibilities of parenthood and a career. The care of my aging parents loomed on the horizon. Now, at seventy, I have graduated, with honors, from the “sandwich” generation, parents peacefully departed after full, well-lived lives, children fully fledged with lives of their own. I am a grandmother of two. Thoughts of mortality now have the time and opportunity to slither from the depths of my mind. They hover patiently at the periphery.

Decisions need to be made about my remaining time. I don’t want to make my parents mistake. They did not embrace technology beyond the clicker on their TV – no cable, no internet and had nothing to entertain them as they transitioned to a sedentary life. My father could have spent hours researching his passion of antique cars, my mother would enjoy witty emails with remote friends. What technology should I keep up with? How about a Twitter handle, an Instagram feed? What will sustain me for the long haul? When will it be too late to start?

An offensive genre of books gleefully proclaims, “The 100 Things [To Eat/Visit/Travel, etc.] Before You Die.” I don’t want anyone else telling me what I’ll be missing. However, my bucket list needs attention. My only item consists of my goal to author a crossword puzzle that is published by the New York Times Sunday magazine. I’ve already nailed the concept. It will be titled R.I.P. The theme answers will be idioms for death, such as “kick the bucket” or “bite the dust.” I hope that the New York Times will publish it on Memorial Day.

Ensconced in the senior generation, I’m at an age where a friend advises me to get to know my doctor better because inevitably I will need his services more. Fortuitously, I have had few encounters with the medical profession. Over the past seventy years, I have broken a leg, an arm and a rib (not all at the same time), have had two benign breast biopsies and have had surgeries for an obstetrical mishap and a stone-laden gall bladder. A pretty decent record that I’m proud of, but I recognize that I’m heading into a decade where death will seem increasingly less untimely.

My mother, at my age now – or to give myself a bit of breathing room maybe in her mid-seventies – shopped for a wardrobe suitable for funerals, “since I will be going to so many more.” Any moment of forgetfulness, previously easily dismissed, now acquires an ominous aura – perhaps flailing to recall the word etui, an essential piece of my vocabulary built on a 50-year history of the New York Time Crossword puzzle., a persistent cough, a skipped heartbeat, a splotch of blood where it doesn’t belong. So far so good.

I look down at my socks, decorated with birds on a wire. The jagged outline of a troubled toenail strains at the fabric succumbing to the planned obsolescence of novelty socks. They won’t last the summer. My living room is filled with images of birds, some gathered on my own, but many are gifts from friends who know my interest. My son once counted over 50 birds in the room, but he inflated the number by counting every bird in a flock of sandhill cranes.

A hutch filled with ceramic birds sits on the mantel. Many years ago, I glued an aspirin to one eye as part of a rousing “hide in plain sight” game for a large family gathering with many young kids, now all grown up. We haven’t played the game in years, but the aspirin is still there, as is the penny glued to the eye of a copper bird statue on the table next to the ottoman.

I wonder what will happen to all these birds when it comes time to dismantle this house. Will anyone play the “hide in plain sight” game again or wonder why there is an aspirin glued to a bird’s eye?

Our dining room contains portraits of my triple great grandparents, salvaged from the attic of my uncle’s garage.

I had recently stayed in a bed and breakfast whose dining room featured similar portraits. When asked about their ancestors, the owner told me she had picked up the pair at a flea market to enhance her Victorian theme. I didn’t want my triple greats to become random tchotchkes. I removed the portraits from the impending dumpster, repaired them and hung them in my dining room. One 32nd of my DNA can be traced back to these pioneers who left their farm in upstate New York to settle in Illinois. However, I sense that any connection to these folks has become so tenuous that it is unlikely they will escape the dumpster on the next go-around. They take up valuable wall space.

I became a compulsive quilter during the pandemic, completing thirty quilts in the past two years. I’ve given away many as gifts to friends, as wedding gifts or contributions to silent auctions, but keep my favorites for myself. What will become of them? I have no control over how anyone chooses to remember me or my possessions, I do hope that my more creative improvisational quilts will be passed on to future generations.

Concessions to age accumulate. I always check bags on an airplane, fearful of dumping my overpacked roller bag on the head of a fellow traveler. We no longer replace the heavy storm windows on our own but dragoon a likely candidate passing through – a hearty nephew, younger friend, or a repurposed tradesman in exchange for a quick and grateful tip.

Reading a book this afternoon is another concession. I don’t ever recall seeing my mother read a book. She was a bright and curious woman but focused on physical and social activity. She collected all her projects in a notebook embossed in gold with the title, “Woman of Action.” Reading in the afternoon would suggest that someone had a serious case of not enough to do. She would say, “it’s a beautiful day, why don’t you get outside?” Aside from violent weather, she considered every day a beautiful day wasted on sedentary pursuits.

I still carry this guilt, particularly since I will surely fall asleep. A nap in the middle of the afternoon would have been anathema to my mother. The book is an important prop, it keeps me sitting up and makes the nap seem like an inadvertent mistake. I choose a hard-back book because it lends a certain gravitas to the tableau. A magazine, (and God forbid a People magazine) would double down on indulgence, a sight unfit for public consumption. I align the spine of the book on my sternum. The equal weight pressing on both sides of my rib cage feels like a comforting and protective hand.

An elder friend/mentor of mine forwarded me the link to “WeCroak,” a website focusing on mortality. The website explains:

“The WeCroak app is inspired by a Bhutanese folk saying, ‘To be a happy person, one must contemplate death five times a day.’ Each day, we’ll send you five invitations to stop and think about death. Our invitations come at random times and at any moment, just like death.”

I’m momentarily tempted, but the app requires a two dollar per month subscription. At the onset of my eighth decade, I see no need to offer a paid encouragement to mortality to step forward from the shadows for a full-frontal view. The meager website following of 175 subscribers – within the range of family and friends – suggests that the bigger world of strangers shares my reaction.

Several years ago, my son Ned was traveling on a slow train through India, seated next to a proselytizing Hindu determined to convert him. He kept asking Ned about his thoughts of the afterlife. Ned stopped the interminable harangue with the simple statement, “I’m willing to be surprised.”

I could spend quality time with deep philosophic thoughts as so many others have – how to take advantage of the time that is left, the death moment itself, how people will remember me, and how long will that memory be retained by future generation. Not today. I don’t have the emotional wherewithal to do more than skitter around mortality’s fringes. “I’m willing to be surprised” is the perfect solution at this very moment. I lean back and feel the gentle spring sun. A breeze riffles the pages of my book. I close my eyes.

Follow Liza Blue on:Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Ruminations on entering the eighth decade of life.

Follow Liza Blue on:1. Egyptian Cotton

Bed, Bath and Beyond wants me to believe that sheets made of “Egyptian Cotton” are the epitome of luxury and that my bed partner and I are worth the price bump. They tell me that Egyptian cotton is synonymous with “comfort, opulence and sophistication, the perfect indulgence for snuggling up, getting comfy and letting your cares fall away.”

How much is real, how much is hype? Is this another marketing ruse for dumb Americans who fall for the allure of an exotic provenance? And what does “Egyptian” mean, in fact? Does it refer to a specific variant of cotton, or any kind of cotton that happens to be grown in Egypt?

High luxury cotton is referred to as “extra-long staple” (ELS) cotton and can be grown in Egypt, but not exclusively. The longer and thinner ELS fibers result in a durable fabric with a silkier feel. However, poor quality cotton is also grown in Egypt and may be blended with ELS cotton. Therefore, labeling something as “Egyptian” is essentially a meaningless marketing term, though more recently the Egyptian government has tried to create an industry standard based on DNA testing to verify ELS cotton. In the US, ELS cotton may be trademarked as the luxury cotton brand “Supima.”

Web sites promoting Egyptian cotton, struggling to find a point of difference with other countries of origin, often point out that Egyptian cotton is “delicately hand-picked with loving care” to prevent clumping. As quaint as this description might be, it also carries with it the putrid whiff of slave labor in the American cotton industry. If not slave labor, then exploitative labor. In Egypt, this translates to child labor where children work grueling hours picking bugs off the growing cotton.

2. Thread Count

Thread count is the companion marketing ploy for sheets, exploiting the American belief that more is better. There are two different types of weaves – the basic percale, which is one fiber over and one under, and the silkier sateen, which is one fiber under and three over.

Thread count represents the sum of the vertical warp and horizontal weave in a square inch of fabric. The higher the thread count, the softer and more durable the sheets – up to 50 years – but frankly I don’t want to inherit Granny’s sheets.

Sateen is more loosely woven and susceptible to snags, and thus the thread count is generally higher than percale particularly if fine threads are used. For percale the average thread count is 180, for sateen 300 to 600. Anything over these thresholds is unnecessary and pure marketing. Additionally, it is likely that the manufacturer is fudging the numbers by twisting more than one thread into the ply, thus doubling the thread count.

3. Triple washed lettuce

Bagged lettuce typically includes the claim that it is “triple washed.” I immediately consider that “wash” is an umbrella term that includes spritzing, sprinkling, rinsing, dousing, dunking and scrubbing. Which one is it? YouTube videos of industrial lettuce washers suggest that “perfunctory spritzing” is an accurate description. A thick jumbled layer of lettuce is loaded onto a conveyor belt that quickly passes under three closely spaced but separate pipes spraying water. There is no agitation, dunking or any guarantee that all the leaves get wet, much less three times.

It is a common misconception that triple washing is designed to eliminate bacteria, such as E. coli. Nope. Food-borne illness is most often introduced in the field due to contaminated irrigation water. Washing at the processing stage only removes dirt and other debris embedded in leafy lettuce curls. In fact, this washing step may increase the risk of food borne illness through cross contamination carried from the field.

If this is the case, shouldn’t we all be washing our lettuce at home? Again no. The FDA points out that we are all dirty and unreliable slobs. Our counters, cutting boards, hands, sneezes and coughs pose a greater risk of cross contamination.

Lettuce-growers love the word “triple washed” since it suggests both a higher level of safety (which it doesn’t) and feeds into American’s love affair with convenience.

4. Triscuits

In my youth, cracker options were limited to Triscuits or Wheat Thins. Individuals and entire families had staunch preferences. Wheat Thins were preferred by those who appreciated their sweeter taste, Triscuits were praised for their sturdier construct ideal for dipping and cheese. The two were inseparable, the Bert and Ernie of the cracker aisle.

Fifty years later it’s an entirely different story. As new products flooded the market, marketers realized that they had to increase the visibility of the humble cracker. Instead of one flavor of Triscuits, there are now 18 different options, ranging from “balsamic vinegar” to “avocado, cilantro and lime.” Aside from the flavors, shoppers can choose between different shapes and sizes.

Triscuits are no longer nestled up to a companion box of Wheat Thins. The display consumes four rows of shelves, extending from knee to forehead level. Yes, the number of options might expand the market, but this strategy has the added bonus of crowding out smaller or innovative brands struggling to get a toe hold in this competitive market. As the Triscuit product line expanded, grocery stores realized that manufacturers would pay for the hotly contested real estate of eye level shelf space. Even more competitive is the fixed size of the freezer case or the check-out lane filled with impulse purchases. In the 1980s, grocery stores started charging “slotting fees” to claim shelf space for those willing to pay for it. These fees are an important source of fixed income for the grocery store, which operates on slim margins. Once the product is slotted on the shelf, the store can charge a yearly fee to keep it there, similar to rent for a high-end apartment. The grocery store can extract more money by charging for product inclusion in their flyers or demanding free product for “buy one get one free” promotions. All of these fees are of course passed on to the consumer.

The unsuspecting shopper may stand in rapture in front of the Triscuit display, thinking that only a great country like the US could offer 18 different flavors. When I stand there, I think that I don’t need a cracker sprinkled with pixie dust suggesting cilantro and lime. I want something new and exciting, but sadly realize that I am a pawn in a hidden, complex, and devious system designed to favor the behemoth manufacturers who can pay to play.

5. Flushable

The market for “wet wipes” or “baby wipes” exploded in the 1990s, responding to parents’ interest in a more durable wipe imbued with lotion, fragrances and disinfectants. The market then expanded to include any kind of personal hygiene beyond the tender skin of baby bottoms. For example, “Dude Wipes” are specifically marketed to men based on their larger size and more horsepower compared to flimsy toilet tissue. The product was profiled on Shark Tank. Mark Cuban, one of the judges, became an investor and showed up in one of their ads.

Tapping into Americans’ thirst for convenience and disdain for smeared body fluids, manufacturers have gleefully marketed their products as “flushable,” even though wet wipes are specifically designed NOT to disintegrate like toilet paper. Without a standard definition, marketers can use the word to describe anything that could be gagged down a swirling bowl. In this context my niece’s sock could be accurately described as “flushable,” even though several days later it resulted in a burbling excremental experience in the sink and shower that my family has tried to forget, but cannot.

Wet wipes can have the same result, clogging both household and downstream sewer systems, contributing to repulsive accretions of solidified fat called “fatbergs.” It is estimated that extracting fatbergs costs US utilities about one billion dollars annually.

The jousting over the definition of “flushable” has begun, pitting the wet wipe industry against the Federal Trade Commission, which has prohibited the use of the word “flushable” in certain products. However, marketers can sub in alternative wording such as “safe for sewers.” California, Oregon and Illinois have ratcheted up efforts by mandating a “do not flush” logo on wet wipes, though I wish they used a gender neutral icon. Manufacturers have countered these efforts with lawsuits contending that the plaintiffs have not definitively proven that wet wipes are the predominant culprit in fatbergs.

The wet wipes aisle in my local grocery store reveals different packaging approaches. Some wipes have deleted the word “flushable” from their packaging and remain silent on the subject. Others display the “do not flush” logo on the front near where the wipe is dispensed, others bury it on the back of the package. Some wipes take an environmental approach, noting that their product is “plant-based,” probably bamboo, contrasting with wet wipes that are made with microplastics. However, this feel-good designation has no bearing on flushability.

Then we have the example of “Dude Wipes” that encourage men to abandon all use of toilet paper. Their package proudly states that their product is flushable. Few will notice the disclaimer in itty bitty font on the back of the package, noting that their wipes should not be flushed if against the law, if there is fat or grease in the drain, or if consumers are unsure of their system capabilities.

Regardless of any regulations, manufacturers can feel smug in the knowledge that the marketing efforts over the past thirty years will have lasting effects. Undoing the learned habits of consumers will take a determined educational campaign. As evidence that there is no cause without an advocacy group the Responsible Flushing Alliance has risen to the challenge.

Follow Liza Blue on: